Welcome

By David Harmon, M4

I can still smell it. No, not the necrotic tissue on the diabetic’s gangrenous leg. No, not the vomit of a disoriented head-trauma patient. No, not the smell of post-anesthesia diarrhea. The anatomy lab. The smell of “preserved” tissue was so potent that long showers and hours of scrubbing couldn’t get rid of it, and date nights turned into awkward conversations about “body odor.” I honestly believed those long afternoons in the noxious anatomy lab would never end.

Incoming M1s attending Disorientation Camp during the summer. Photo by Sarah Fulton, M2.

Then I blinked. Somewhere between then and now lies a collection of foggy mental snapshots: spending long days trapped in a lecture hall or the anatomy lab; napping during afternoon lectures; considering future backup plans if med school didn’t work out; the seemingly eternal lonely days spent studying for overwhelming USMLE exams; seeing patients alone for the first time; pretending to know differential diagnoses; performing my first delivery (who knew babies were that slippery?). Sometimes, I stood by, helplessly watching death shatter a family’s already sparse hope. But, somewhere along the way all the studying came to life—a patient needed me, and I was actually able to help. I had only exasperatingly learned BLS/ACLS techniques for recertification, forgetting I could actually save a life. Now I contribute as a member of the team.

I think about how I’ve changed since arriving at medical school. I have not been broken, just tested. Not jaded, but more understanding. I perceive how people, patients, doctors, and students hurt. I’m stronger. I’m inspired. And honestly, a little scared. This strength did not come from sitting still. It came from spending long nights in anatomy lab, surviving a week of trauma surgery night shifts, practicing sutures even after sticking myself a time or two, reassuring parents of sick kids, and running to codes. I have bonded with my classmates, my residents, and of course, my patients. Being honest, and taking the time to actually know them, helped me truly learn what pain and hope meant. This path through medicine will change you. It will form you. It may not be easy, but it will be worthwhile.

Disorientation Camp counselors (M2s) during the summer. Photo by Sarah Fulton, M2.

To my fellow M4s: let us not grow weary. We have one more push to the end. We have made it this far. Let’s finish strong. Don’t stop working.

To the M3s: I know clerkships are grueling. Honestly, you may be more tired than you have ever been in your life some days. Sometimes, you just can’t flip your sleep schedule to nights (or flip back to days in my case). But this year is the single biggest opportunity you have to truly invest in patients, a resident team, and your future field of study. Don’t sit still.

To the M2s: Clerkships are just around the corner! Life will get more exciting soon, I promise. Before then, overwhelming work and exams sit in the way. I know this is intimidating. I know this is frustrating. Keep going. Don’t lose sight of the end goal.

To the new M1s: WELCOME! I hope to one day meet you personally. You are entering a time of your life that will shape you in so many ways. The payoffs are innumerable, and the experience is invaluable. Equally horrified and elated may describe many of you, while others may be a little more relaxed (I was more of the former). You selected this path for one reason or another, and, hopefully, you are more than excited to be here. Don’t ever lose that excitement.

Giving Up Giving Up

By Radhika Shah, M1

We, as humans, are an encouraging species. “Follow your dreams!” we say. “Never give up!” As easy as it is to say, is it just as easy to do?

It wasn’t until I started applying to medical school that I started to question whether I was truly capable of “following my dreams” or not. When I applied the first time, I had just started my last year of college and I was confident that I’d be able to transition into medical school immediately after graduating. Several of my fellow pre-meds had done the same. I had unwavering encouragement from my family, friends, peers, and mentors. They all believed in me and “knew” I would meet with success very soon. “How could they not accept someone like you?!” resonated in my head. Surrounded by positivity, I felt great hitting that submit button. Now all I had to do was wait for interviews, right?

Wrong. I watched over my inbox like a hawk, day in and day out. September passed, then October. Before I knew it, it was Thanksgiving. “Maybe they just haven’t gotten to my application yet,” I thought. “Well, I DID apply later in the cycle, so it’s normal for this to happen,” I further reassured myself. January rolled around, and all at once I received those dreaded rejection emails—the emails that suck your soul out like the dementors of Azkaban.

I got over it, did some file reviews with schools, received mostly positive feedback about my stats and experience and was told to apply again. They advised me to edit sections of my application and reclassify certain activities. Biggest improvement needed on my application? Apply early. So I did.

Paw Print Flowers. By Carolina Orsi, M1.

My application was complete by mid-May (extremely early relative to other applicants). To fill my gap year, I took on another shadowing opportunity and treated it as a nine-to-five job, keeping myself busy. I felt significantly more confident than I did the previous year. “I did exactly what they told me to do, so I have nothing to worry about,” I told myself. The months passed again—faster, it seemed. The interviews never came. I waited and waited some more. Everyone around me kept positive: “You’ll definitely get in this time around” and “Don’t give up!” My self-esteem, however, dwindled. What did I do wrong? Why couldn’t I even get an interview? Am I not cut out for medicine? Why could they not see that there’s nothing more that I want than to devote my life to taking care of patients? I was plagued with feelings of self-doubt and frustration.

December came and I lost hope. Becoming a physician was my dream from a young age, but the odds did not seem to be in my favor. I was told by many to consider PA school or take the LSAT, maybe even the DAT. The same people who were so encouraging in the beginning now lost faith that I could pursue my dreams. Many of my friends had already been accepted to medical school, but here I was, on the brink of rejection a second time. I felt humiliated and like I had let everyone down. I never had a plan B. Medicine had been my only option, my only dream. I decided to schedule file reviews again to see where exactly I went wrong.

What do you call a question without an answer? My file reviews. Every single admissions officer: “I don’t see why you wouldn’t have gotten an interview, everything seems great.” Perhaps it was just the sheer capacity of qualified applicants that prevented me from moving forward. I felt lost and scared. If there was nothing significant to improve upon, should I even consider applying again? Was this it?

As I mulled over those questions, I came to a realization of sorts. I was reminded why I chose to pursue medicine in the first place—my future patients. I wasn’t applying to medical school so I could become a physician, I was applying because my patients needed me. To let a few rejections stop me from doing that would be a disservice to those patients. Just because it’s hard doesn’t mean it’s impossible. I can’t be selfish and ignore their needs. My motivation transformed immediately. It wasn’t about me; it was about them.

I decided to apply to the University of North Texas Health Science Center master of medical sciences program. My family was extremely supportive of my decision, and I figured that successfully completing a fast-paced, rigorous graduate curriculum would show medical schools that I really was serious. I then submitted my application without reservation.

I waited again. Many of my friends in the program began to receive interviews in July and August. Thanksgiving was coming and I began to lose hope. However, as I was sitting in class one day, I decided to check my email. To my surprise, I received an email from a school I applied to. Extremely curious, I opened it and immediately began to cry.

It was an interview invitation. My first ever interview. I was so happy that I couldn’t contain my emotions. My friends asked me what was wrong and I smiled. They knew what had happened, and I got an overwhelming response of love and congratulations. The next few weeks I received a couple more invitations from schools. I felt more accomplished than I had ever felt before in my life. Though the process was not over, it finally felt like my dream was attainable.

Now that I am finally a first year medical student at Texas A&M University College of Medicine, I look back at my reapplicant experience and remember how hard it was to get here. I felt hopeless and incapable. I lost support from people who I thought cared. I fell behind. So why am I telling my story, you ask? Because giving up should never be an option. Regardless of how impossible it may seem to fulfill your dreams, if you really want something, you should go for it. If no one else believes in you, believe in yourself. Only when you believe in yourself can you convince other people to believe in you. Because I did this, I can proudly say I will be able to treat and care for patients for the rest of my life, and that truly makes me the happiest person in the world.

A Year In Review

By Amanda Edinger, M2

I ran across a quote yesterday. It was on the back of a book I bought but won’t read for another month or two. Or three. The quote said, “If we can’t have everything, what is the closest amount to everything we can have?” It reminded me of the first year of medical school. As if I needed reminding. As if school isn’t all that I think or do. But as I read, I couldn’t help but think that it could just as easily read, “If we can’t know everything, what is the closest amount to everything we can know?” This quote is the first year of medical school captured in a sentence.

I came into my first year excited and ready to soak up as much information as possible. Everything was new. My new white coat was crisp, clean, and barely worn. My scrubs were just beginning to absorb the inescapable, lingering smell of phenol. My brain was just beginning to comprehend the complexities of the human body. Suddenly four years didn’t seem so long. Each day, I grasped at the information being thrown at me, hoping that I catch more than I let pass by. Slowly, just like every doctor before me, I began to learn and grow.

Now it’s second semester. I’ve conquered the mountain that is anatomy. I’ve studied slides until I dream in pink and purple. On to better things. After learning the physical exam, I am assigned my first real, living patient. But instead of a name, I’m given a room number. I walk the unfamiliar halls of the hospital until I come upon the right room. After I check then double check that I’m in the correct place, I knock on the door. I begin to introduce myself to the patient and ask for permission to take a brief history and physical exam. The patient doesn’t appear to hear me, so I ask again. No response. This seems strange, but I’ve never met this patient. “Maybe this is her baseline,” I think to myself. The nurse comes to give the patient her medications, but the patient doesn’t respond to the nurse either. Suddenly, the patient’s arm starts to move rhythmically back and forth. The movement spreads to her body. Her face contorts into a silent scream. Her arm stops moving and becomes stiff. It takes me a few beats to realize that I’ve learned about this. It finally begins to come together; the patient is having a seizure. I freeze. Despite the seemingly endless structures, innervations, and facts I have memorized so far, I haven’t a clue what to do next. I’ve been in school for nearly eight months, yet I don’t know most of the drugs that the real doctors order when they finally rush into the room. How can I have learned so much and still know so little?

I’m assigned a new patient. I begin to take the history. The patient begins to rattle off his symptoms. I translate his English into medicine in my head: dyspnea on exertion, PND, orthopnea. I move to the physical exam: laterally displaced PMI, pretibial edema, bibasilar crackles. “I know this one,” I think to myself. I’m amazed at how exactly his symptoms match the ones I’ve memorized. I realize that the patient has heart failure. I even know the drug the nurse came to give him, furosemide, a loop diuretic. As I drive home from the hospital, I feel a mix of concern for the patient’s condition and awe at being able to diagnose it. I realize that this is but the beginning of a tapestry of stories, patients, and conditions that I will encounter. But still, I can’t help but smile because I know that I’ll never forget how heart failure presents. I’ll remember this patient, his face, his symptoms, his story.

Now I am approaching the end of my first year of medical school. I’m simultaneously fascinated and frustrated by the vast nature of modern medicine. Friends and family ask me, “How is school going?” “Medical school is difficult,” I want to say. Medical school is confronting the reality that imperfection will always be present where perfection is due. It’s like continuing to drive your car down an unfamiliar highway with your low fuel light on and praying you don’t run out because you’re not sure where you will find the next gas station. There is a constant uneasiness that you might not make it, mixed with excitement for the moment when you will finally arrive at your destination. “School is good,” I reply.

Refresh

By Sara Benitez, M2

View of the rain forest from a Costa Rican Airbnb. Photo by Sara Benitez, M2.

The first year of medical school felt like a marathon, and it was difficult to find the time to catch my breath. Even after our last exam of the year, I still found myself running as I drove to the airport to catch a flight to Costa Rica. That Friday was a long day, but when I woke up the next morning and saw the view from our Airbnb, I knew this was exactly what I needed.

On Saturday, we drove to the town of Monteverde, where the famous Cloud Forest Reserve is located. Our Airbnb there was located in the middle of the forest; I fell asleep to the sound and chill of the rain and woke up to the chirping of birds on Sunday morning. We took a bird watching tour at the crack of dawn, which turned into a tour of the whole forest and wildlife. I had never seen such vibrant greens in my life, and everything was picture perfect. I looked up and saw the beautiful canopy with monkeys climbing from tree to tree, and throughout the tour I felt like an intruder in their natural habitat. As I was filled with awe at the biodiversity and beauty of the forest, I couldn’t help but feel like such a tiny part of the world we live in. As medical students, we tend to get caught up in studying and working so hard that we forget there is a vast world around us. Feeling small allowed me to look up at the world around me and marvel, serving as a reminder that there is more to life than lectures and sitting at a desk for hours on end.

Moreover, I spent Monday through Friday learning medical Spanish in a town called San Joaquin de Flores and realized that this too was something I needed. Spanish is my native language, and even though I grew up speaking it with my family and still use it while back at home, living in the U.S. has made me more comfortable with speaking English at the cost of losing part of my native language. What I realized throughout my stay is that I have great conversational Spanish, but medical Spanish is more complex than I expected. However, as I learned the intricacies of Spanish grammar, read articles with complex vocabulary, and prepared a presentation in Spanish, I began to fall in love with my native language again. There are words that sound plain in English, and yet, seem to come to life in Spanish. For example, cerebral cortex is “la corteza cerebral” and the peripheral nervous system is “el sistema nervioso periférico.” There is also something special about knowing a language that can allow me to communicate with people of various cultures within the same Hispanic race. One of my favorite parts about Costa Ricans is that they truly believe in their commonly used phrase or salute, “Pura Vida,” which literally translated means “Pure Life” and connotatively refers to having a positive attitude and living a simple life. Throughout my short experience learning medical Spanish, I realized the work ahead of me and gained a better appreciation for my native language.

Photos from Costa Rica. By Sara Benitez, M2.

Though Costa Rica provided the break from medical school that I needed, it also revived my passion for medicine and inspired me to believe in my medical potential. I spoke to a doctor about my interest in neurology, and she told me that we need more compassionate neurologists because the ones she refers her patients to are not very understanding of the patient’s condition as a whole. One aspect of medicine that drew me to the field was the impact I could have on people’s lives, not only physically, but emotionally. I could be there for them and their families during times of need. The fact that someone told me the qualities I believe I have are needed in medicine made me ashamed of the self-doubt that first year brought with it, but it encouraged me to remember why I even went into medicine in the first place.

Though Costa Rica already gave me more than I could ever imagine, it still gifted me with another experience when I met an inspiring person. Gail Nystrom, a former Peace Corps volunteer, saw a need for health care in a Costa Rican slum and decided to take action. Running on a great desire to serve, she helped establish an amazing medical system for the underprivileged around the area. The community now has health care access via home visits by nurses who establish the needs within the town and triage clinic visits to those most in need. The people of the area also have access to a clinic with various resources and personnel, including a psychiatrist and nutritionist. As if this were not enough, Nystrom helps run a pre-school for children of the community and is actively involved in various other community projects not related to medicine. Meeting her made me realize that all it takes to make a difference is a willing person who can recognize the needs around them and is brave and caring enough to take action.

While the marathon of the past year was challenging, my trip to Costa Rica allowed me to reflect on many things. Most importantly, remember to slow down and refresh the page you seem to be stuck on, and you’ll be amazed at what you discover about yourself and the world around you. ¡Pura Vida!

Forgotten Patriots

By Rahul Devroy, M3

Crafted popsicle stick American flags. Photo by Rahul Devroy, M3.

Fourth of July, a time of patriotism, camaraderie, and gratitude. This year I had the good fortune of spending the holiday at an Alzheimer’s care facility and had the pleasure of meeting many remarkable people. Initially, my medical student instincts got the best of me as I started “pseudo-interviewing” to classify early, intermediate, or late stage disease progression; were amyloid plaques aggregating as we were speaking? However, I quickly realized that getting to know and befriending the patients were better approaches than obtaining a review of systems.

In keeping with the theme of Independence Day, we spent one afternoon making handicraft flags. Using popsicle sticks and watercolors, we filled the corridors with our flag art. During the activity, some of the patients spoke of July Fourths of yesteryears. As I listened to their stories, I took a step back and realized that these people were members of the Greatest Generation; they had lived through World War II, the Civil Rights Era, and countless other historical milestones of the twentieth century. Their hard work and sacrifices helped raise our nation to what it is today. They raised the flags we were decorating. It felt tragic to me that they probably could not recount the huge events that they had intimately been a part of. As a medical student, I knew what to expect from these patients, but it was another thing altogether to actually be with them. To me, forgetting that an event happened was sad in itself, but the loss of an individual’s personal insight, commentary, and story was the real tragedy.

As I left that day, I thanked all the men and women with whom I had worked. I received many responses of “No, thank you!” along with a few looks of confusion, but I knew their sacrifices even if they could no longer remember. Whether it was through active military service or by serving 30 years as a teacher, they each contributed in their own way. I was proud to be privileged enough to spend my July Fourth with these patriots.

Stroke Out

By Sonia Ozurumba, M4

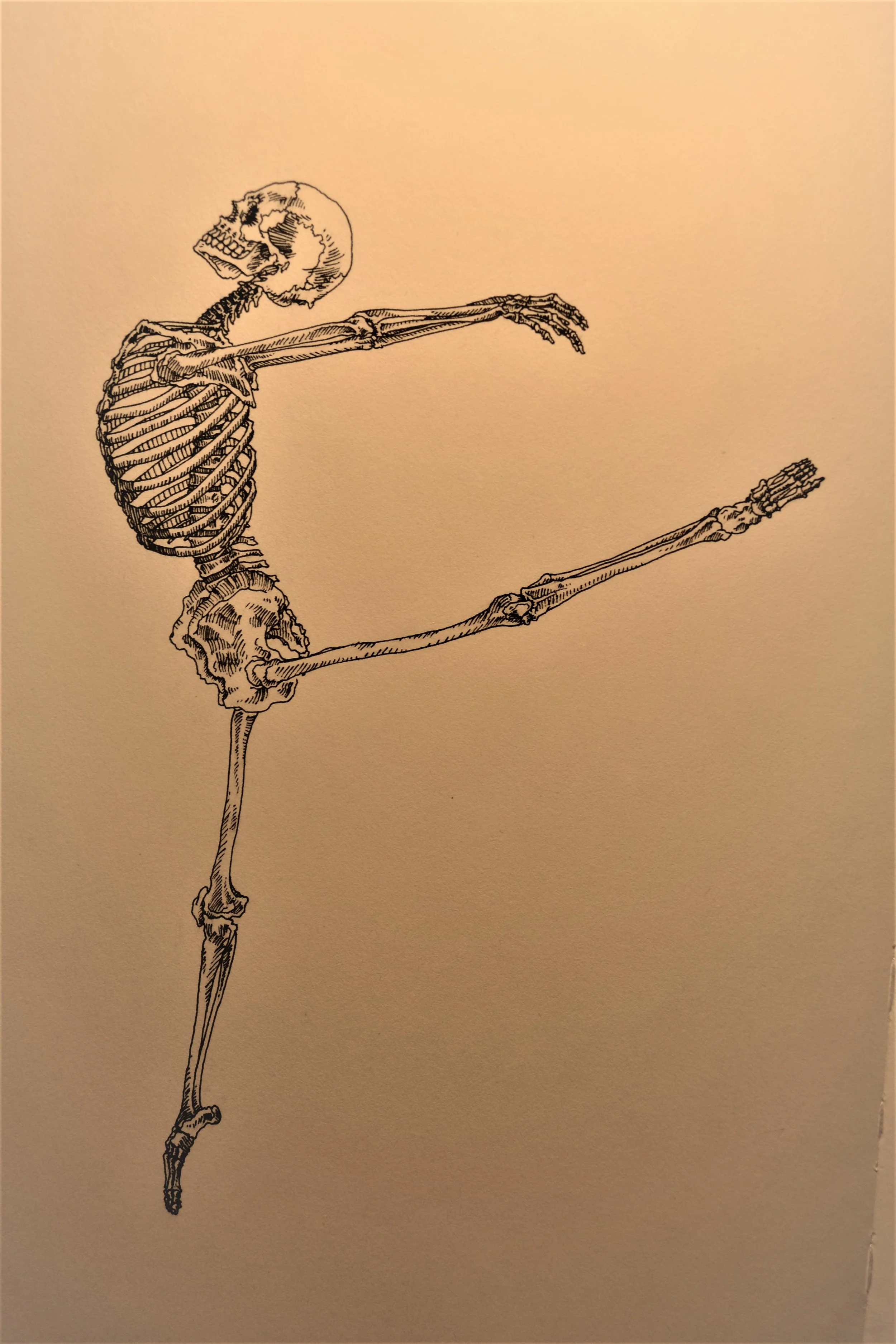

Artwork by Timothy Fan, M1.

You never think about the end till it comes knocking. You never know how well you lived till your health tells you to examine your life. And you never know how well you loved till death tells you it's over. When you first hear it, it never sinks that deep—that piece of bad news, that word you never want to hear. To us, that word was “stroke.”

It was hard to believe it. We never knew what it implied, I thought there was hope. I mean, we were advanced, weren’t we? But that day, when I went to the hospital to see my grandmother lying down on the bed, I knew it was over.

Even though I prayed with my heart, my eyes could not forget what I saw. My eyes… I wished I had had them closed. There was nothing worth seeing, there was no equipment. There was no CT machine to do a scan of the brain, no one was saying anything. There wasn’t even any equipment for simple leg elevation to reduce the edema. Just a water-filled glove underneath the heels. How about a pillow? I was appalled. Where were the doctors? Why were the nurses coming in and out? Nothing was done to change the story.

This was our level. This was our hope. How can healing be spoken? It wasn’t a place of healing. Maybe we were in the wrong place. Maybe we took a wrong turn. Or maybe this was just reality. This was the best hospital in Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. Nothing could be done to change the story.

This is what we had to face, and in this time, we chose to live. Live life just as it was: we smiled when we could, prayed when we could, and cried when it was over.

Hanna Fanous, Copy Editor

Garret Hisle, Copy Editor

Hasan Sumdani, Copy Editor

Anandini Rao, Copy Editor

Puja Panwar, Chairman of the Board

Alexander Hsu, Managing Editor

Hailey Driscoll, Acquisition Editor

Bevan Johnson, Design Editor

Britton Eastburn, Design Editor

Submit to us!

Share your work with the Texas A&M medical school

community. Please email us at COM-synapse@tamhsc.edu to submit work, make suggestions, or ask questions. We

are looking forward to hearing from you!

THANK YOU

A special thanks to...

Dr. Karen Wakefield for being our faculty editor,

Dr. Barbara Gastel for serving as editorial mentor,

and Dr. Gül Russell for providing support and encouragement.